Perfume, excerpts:

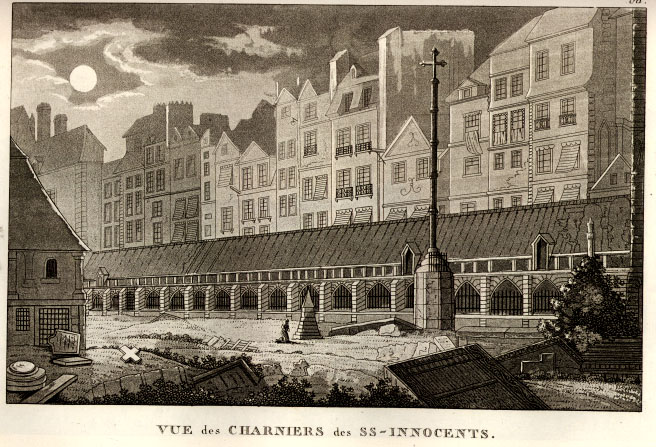

...the stench was foulest in Paris, which was the largest city of France.

And in turn there was a spot in Paris under the sway of a particularly

fiendish stench: between the rue aux Fers and the rue de la Ferronnerie,

the Cimetière des Innocents to be exact. For eight hundred years

the dead had been brought here from the Hôtel-Dieu and from the surrounding

parish churches, for eight hundred years, day in, day out, corpses by the

dozens had been carted here and tossed into long ditches, stacked bone

upon bone for eight hundred years in the tombs and charnel houses. Only

later—on the eve of the Revolution, after several of the grave pits had

caved in and the stench,had driven the swollen graveyard's neighbors to

more than mere protest and to actual insurrection—was it finally closed

and abandoned. Millions of bones and skulls were shoveled into the catacombs

of Montmartre and in its place a food market was erected.

Here, then, on the most putrid spot in the whole kingdom, Jean-Baptiste

Grenouille was born on July 17, 1738. It was one of the hottest days of

the year. The heat lay leaden upon the graveyard, squeezing its putrefying

vapor, a blend of rotting melon and the fetid odor of burnt animal horn,

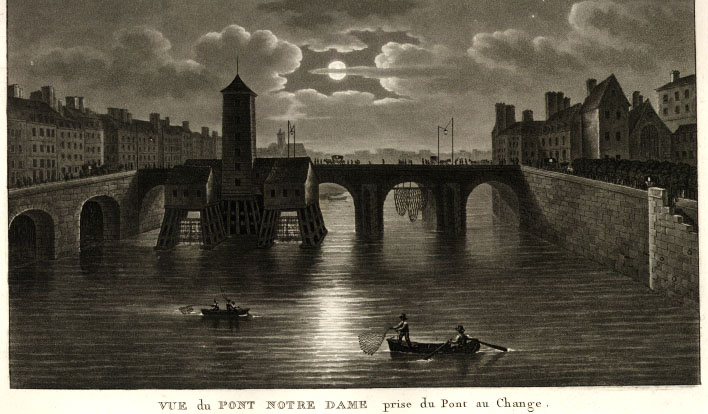

out into the nearby alleys. When the labor pains began, Grenouille's mother

was standing at a fish stall in the rue aux Fers, scaling whiting that

she had just gutted. The fish, ostensibly taken that very morning from

the Seine, already stank so vilely that the smell masked the odor of corpses.

Grenouille's mother, however, perceived the odor neither of the fish nor

of the corpses, for her sense of smell had been utterly dulled, besides

which her belly hurt, and the pain deadened all susceptibility to sensate

impressions. She only wanted the pain to stop, she wanted to put this revolting

birth behind her as quickly as possible. It was her fifth. She had effected

all the others here at the fish booth, and all had been stillbirths or

semi-stillbirths, for the bloody meat that emerged had not differed greatly

from the fish guts that lay there already, nor had lived much longer, and

by evening the whole mess had been shoveled away and carted off to the

graveyard or down to the river. It would be much the same this day...

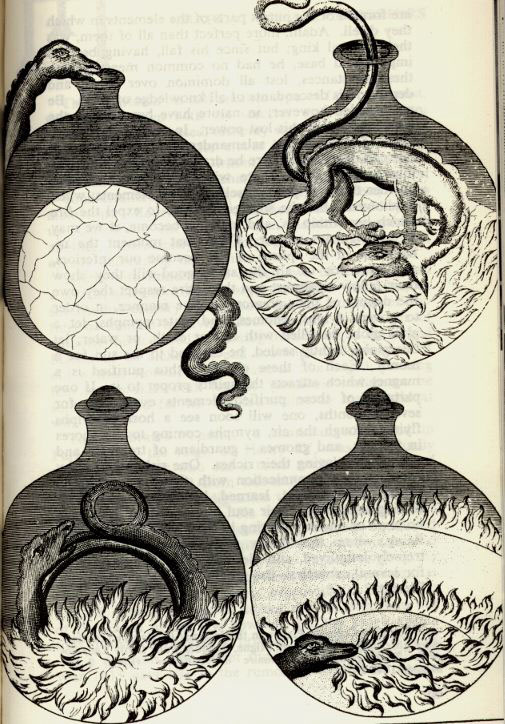

The little man named Grenouille first uncorked the demijohn of alcohol.

Heaving the heavy vessel up gave him difficulty. He had to lift it almost

even with his head to be on a level with the funnel that had been inserted

in the mixing bottle and into which he poured the alcohol directly from

the demijohn without bothering to use a measuring glass. Baldini shuddered

at such concentrated ineptitude: not only had the fellow turned the world

of perfumery upside down by starting with the solvent without having first

created the concentrate to be dissolved—but he was also hardly even physically

capable of the task. He was shaking with exertion, and Baldini was waiting

at any moment for the heavy demijohn to come crashing down and smash everything

on the table to pieces; The candles, he thought, for God's sake, the candles!

There s going to be an explosion, he'll burn my house down . . . ! And

he was about to lunge for the demijohn and grab it out of the madman's

hands when Grenouille set it down himself, getting it back on the floor

all in one piece and stoppered it. A clear, light liquid swayed in the

bottle— not a drop spilled. For a few moments Grenouille panted for breath,

but with a look of contentment on his face as if the hardest part of the

job were behind him. And indeed, what happened now proceeded with such

speed that Baldini could hardly follow it with his eyes, let alone keep

track of the order in which it occurred or make even partial sense of the

procedure.

Grenouille grabbed apparently at random from the row of essencesin

their flacons, pulled out the glass stoppers, held the contents under his

nose for an instant, splashed a bit of one bottle, dribbled a drop or two

of another, poured a dash of a third into the funnel, and so on. Pipette,

test tube, measuring glass, spoons and rods—all the utensils that allow

the perfumer to control the complicated process of mixing— Grenouille did

not so much as touch a single one of them. It was as if he were just playing,

splashing and swishing like a child busy cooking up some ghastly brew of

water, grass, and mud, which he then asserts to be soup. Yes, like a child,

thought Baldini; all at once he looks like a child, despite his ungainly

hands, despite his scarred, pockmarked face and his bulbous old-man's nose.

...There was just such a fanatical child trapped inside this young man,

standing at the table with eyes aglow, having forgotten everything

around him, apparently longer aware that there was anything else in the

laboratory but himself and these bottles that he tipped into the funnel

with nimble awkwardness to mix up an insane brew that he would confidently

swear—and would truly believe!—to be the exquisite perfume Amor and Psyche.

Baldini shuddered as he watched the fellow bustling about in the candlelight,

so shockingly absurd and so shockingly self-confident. In the old days—so

he thought, and for a moment he felt as sad and miserable and furious as

he had that afternoon while gazing out onto the city glowing ruddy in the

twilight—in the old days people like that simply did not exist; he was

an entirely new specimen of the race, one that could arise only in ex hausted,

dissipated times like these....

Baldini was so busy with his personal exasperation and disgust at the

age that he did not really comprehend what was intended when Grenouille

suddenly stoppered up all the flacons, pulled the funnel out of the mixing

bottle, grabbed the neck of the bottle with his right hand, capped it with

the palm of his left, and shook it vigorously. Only when the bottle had

been spun through the air several times, its precious contents sloshing

back and forth like lemonade between belly and neck, did Baldini let loose

a shout of rage and horror "Stop it!

...even as he spoke, the air around him was saturated with the odor

of Amor and Psyche. Odors have a power of persuasion stronger than that

of words, appearances, emotions, or will. The persuasive power of an odor

cannot be fended off, it enters into us like breath into our lungs, it

fills us up, imbues us totally. There is no remedy for it.

Grenouille had set down the bottle, removing his perfume-moistened

hand from its neck and wiping it on his shirttail. One, two steps back—and

the clumsy way he hunched his body together under Baldini's tirade sent

enough waves rolling out into the room to spread the newly created scent

in all directions. Nothing more was needed. True, Baldini ranted on, railed

and cursed, but with every breath his outward show of rage found less and

less inner nourishment. He sensed he had been proved wrong, which was why

his peroration could only soar to empty pathos. And when he fell silent,

had been silent for a good while, he had no need of Grenouille's remark:

"It's all done." He knew that already.

|